Angular Service Worker, push notifications, and badges

Pushing notifications to a progressive web app using Angular’s Service Worker

· 12 min read

Intro #

For quite some time now, I’ve been busy building my own web app that gives me more insights into my home’s energy consumption. Think of electricity usage from the grid, injecting energy coming from my solar panels, gas usage, historical data, etc. I’ve been wanting to do a little write-up for that a long time now, but, as life happened, it got put aside.

Anyway, one of the things I wanted to achieve for a long time now was to convert my app into a proper progressive web app. One with push notifications.

Goal #

I wish to receive a notification whenever my current electricity usage gets too high. You see, where I live in Belgium, you get taxed depending on the average amount of current you draw in a (non-moving) window of 15 minutes. This value, or a previous higher value, then counts for the rest of the month. A final average is taken over the last 12 months, which is used to calculate the final cost.

This means that one little oversight means you’re paying for that mistake for the upcoming 12 months. The idea of the grid operator is to make you spread your consumption in time, instead of turning on all of your appliances at once.

As I’m monitoring my electricity usage every second anyway, wouldn’t it be cool if my app sent me a notification whenever I’m on my way to set a new monthly “high score”?

Flow #

First off, in order to send a notification, the browser has to ask permission from the user. If granted, the browser returns a subscription object which the back-end will need to actually push messages. However, a (web) server cannot just start sending notifications directly to its users after receiving this subscription. You also need to set up a pair of secure VAPID keys, which contain a public and private key. These keys are used to encrypt the payload you send to the push service and decrypt the payload again when receiving it. It is this push service that will notify the client. While testing, I learned there exist different push services, depending on the device used: Firefox uses Mozilla’s push service, Chromium uses one from Google and Apple also has one of its own.

A notification in itself is a simple JSON object and could look like the snippet below. The only property that’s really required is title but it’s of course more interesting to provide more details to your user.

{

"notification": {

"title": "Hi there",

"body": "There is something happening you should know.",

"icon": "icons/icon-192x192.png",

"badge": 1

}

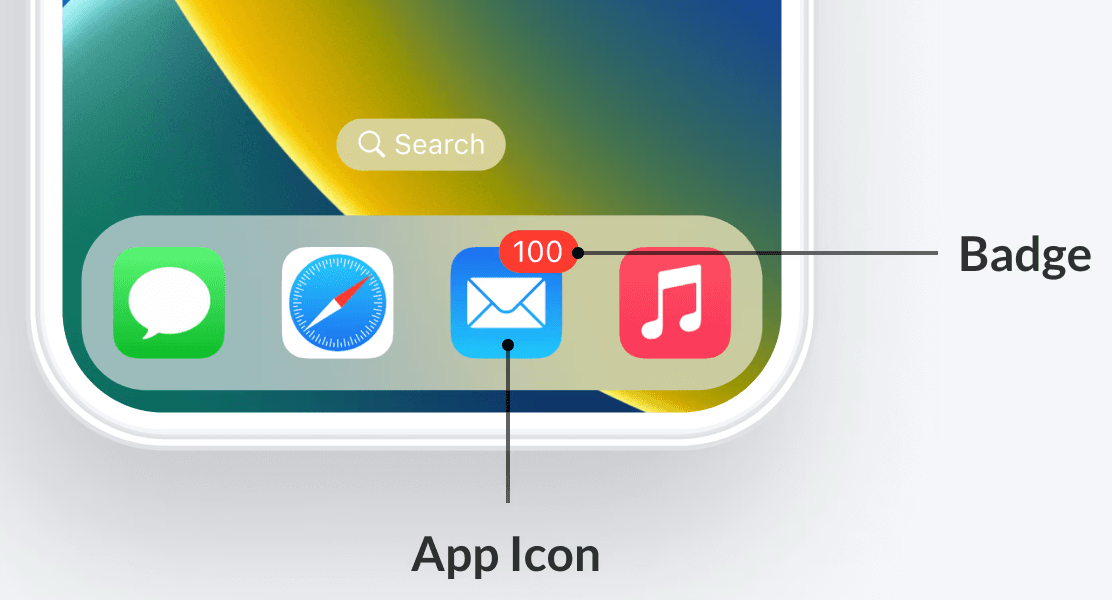

}If you’re wondering what that badge property is, take a look at the image below. If a user doesn’t open your app immediately and notifications keep rolling in, the badge count will only increase, making clear to the user they’re now behind on n notifications. In case you didn’t notice it yet: it’s not the client that automatically takes care of this – in fact, it does very little – but it’s the back-end handling the count, as the notification object originates from there and has to be set in that object.

Back-end #

Let’s first map out the necessary back-end work. To avoid having to sign JWTs myself and deal with all the details, I made use of a library called web-push for Node.js, as that’s the stack of my back-end (together with Nest.js).

After providing the library with your keys – it can also generate VAPID keys for you, or, you use an online generator – it’s then easy to send a notification:

const notification: Notification = {

title: 'Hi there',

body: 'There is something happening you should know.',

icon: 'icons/icon-192x192.png',

badge: 1,

};

const vapidDetails = {

// A subject having `mailto:someone@example.com` is also allowed

subject: 'https://your-domain.com',

publicKey: 'abc123',

privateKey: 'xyz789',

};

await WebPush.sendNotification(subscription, JSON.stringify({ notification }), { vapidDetails });Note that you need to wrap the notification object, and the subscription parameter is something you need to get from the browser. After a user gives consent to enable notifications, a subscription object gets returned, and the client has to send it to some endpoint on your back-end. Very likely, you’ll also want to store it by then because you cannot send any notification afterwards without it. Such a subscription contains the endpoint (of the push service) where the notification will be sent to, along with some authentication parameters. For those wondering, it’s perfectly serializable.

Storing subscriptions #

I once again made use of my all-time favourite database, SQLite, to keep track of all registered subscriptions. The schema below can serve as inspiration. It shouldn’t contain anything you wouldn’t expect.

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS notification_subs (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

endpoint TEXT NOT NULL UNIQUE,

p256dh TEXT NOT NULL,

auth TEXT NOT NULL,

badge_count INTEGER DEFAULT 0,

created_at DATETIME DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);Badge count #

In order to set the correct badge count, you need to know how many unread notifications the user has at that point. I have chosen to also store a badge_count property in my database for each subscription. Every time you want to send a notification to a given client, get the current badge count, increment it by one, put that new value in the badge property of the notification object and send it.

Endpoints #

Registering a subscription #

Recall that the user has to give consent to allow notifications. If granted, they receive a subscription object which has to be sent to the back-end. For brevity, I merged the most relevant controller and service code and omitted other, less interesting code:

@Post('subscribe')

subscribe(@Body() sub: WebPush.PushSubscription) {

const query = `

INSERT INTO notification_subs (endpoint, p256dh, auth)

VALUES (?, ?, ?)

ON CONFLICT(endpoint) DO NOTHING;

`;

this.database.run(query, sub.endpoint, sub.keys.p256dh, sub.keys.auth);

return;

}Once the user has given consent, the same subscription is returned each time the page is loaded. If you set it up so that the subscription gets sent to the back-end automatically when getting the subscription, you should avoid having it added to the database again and again. I chose to counter this on both the front and back-end.

Clear badge count #

If you get the current badge count and increment it when sending a notification, the badge count will, of course, display an ever-increasing number, whether the user has already seen the previous notifications or not. Once the user opens the app, all notifications are considered to be read and thus need to be cleared and set to zero again. This is a very trivial endpoint to implement, involving a simple UPDATE SQL statement, though it might be easy to overlook.

Front-end #

Angular & PWA #

The front-end is developed using Angular and, luckily, they provide a PWA package which adds a schematic to set up the PWA configuration and registers the service worker. Out of the box, Angular’s service worker provides push notifications. This means that whenever my back-end sends a notification, even when the app is suspended, my browser shows a notification. This makes it especially useful on mobile devices.

To set up the service worker so it will handle notifications, I chose to implement it like this:

private readonly swPush = inject(SwPush);

public requestNotificationPermission() {

this.swPush.subscription

.pipe(

take(1),

filter((sub) => sub === null),

switchMap(() => this.swPush.requestSubscription({ serverPublicKey: this.publicKey })),

switchMap((pushSub) => this.http.post(`${this.pushNotificationUrl}/subscribe`, pushSub)),

catchError((err) => {

console.error('Could not subscribe to push notifications', err);

return EMPTY;

})

)

.subscribe();

}The good news was that without much sweat, notifications arrived just fine, while adding to the look and feel of a native app. The bad news was that, for some reason, Angular’s service worker does not handle setting (or clearing) the badge. It just displays the notification, and that was the end of it.

Custom service worker #

Fortunately, you can extend the default service worker Angular provides. Ever since they gave their website a huge overhaul, the documentation has proved to be really useful, I believe. That’s where I learned how to build upon their default implementation.

Extending upon the push event, I came up with the following:

// Import the original Angular service worker

importScripts('./ngsw-worker.js');

(function () {

'use strict';

const setBadgeCount = async (count) => {

if ('setAppBadge' in navigator && count > 0) {

await navigator.setAppBadge(count);

} else if ('clearAppBadge' in navigator) {

await navigator.clearAppBadge();

}

};

self.addEventListener('push', (event) => {

if (!event.data) return;

const count = event.data.json().notification?.badge ?? 0;

event.waitUntil(setBadgeCount(count));

});

})();I have put this file - I named it custom-sw.js - in the src folder. Note that I imported the default worker file first to not miss anything Angular offers by default. Also, note that this file only exists in the build output folder. This means that if you want to test this, you have to build and serve the built files.

Of course, Angular won’t know or use this file until you instruct it to do something with it. There are still two more steps to take.

First, the most obvious step. In app.config.ts, you no longer need to point to the old service worker but to the new one:

provideServiceWorker('custom-sw.js', {

enabled: !isDevMode(),

registrationStrategy: 'registerWhenStable:30000',

}),Finally, when issuing a build, you need Angular to copy the new service worker file to the build output folder. In your angular.json file, specify it in assets. You can find the assets array in the following path: projects.<project-name>.architect.build.options.assets.

{

// ...

"assets": [

{

"glob": "**/*",

"input": "public"

},

"src/custom-sw.js"

]

// ...

}Clearing the app badge #

At this point, I was able to see the badge with its appropriate count. However, when I opened the app, the badge did not go away afterwards. This, of course, makes perfect sense; the back-end is not aware of the user opening the app. Whenever the app gets visible, the front-end should call the endpoint to reset the badge count. I made use of the visibilitychange event that fires whenever a window or tab is hidden or gets visible.

Please note that, just like with the back-end code, I merged component and service code for brevity and left certain parts out.

Also note that I clear the app badge as soon as the user opens the app using navigator.clearAppBadge(). I don’t have to wait for the back-end call to finish. It wouldn’t matter anyway, as the count that has been reset will only be noticeable in a new notification. Moreover, if the user quickly opens and closes the app, making the home screen visible again, the app badge is already removed.

fromEvent(document, 'visibilitychange')

.pipe(

map(() => document.visibilityState),

filter((state) => state === 'visible'),

takeUntilDestroyed()

)

.subscribe(() => {

if ('clearAppBadge' in navigator) navigator.clearAppBadge();

this.swPush.subscription

.pipe(

take(1),

filter((sub) => sub !== null),

switchMap((sub) => {

// In case the user swipes away the app real quick after opening it,

// this call risks being cut off if not using `keepalive`.

// `navigator.sendBeacon` is also an option for this, by the way.

const payload = { endpoint: sub.endpoint };

return this.http.post(`${this.pushNotificationUrl}/reset-badge-count`, payload, {

keepalive: true,

});

})

)

.subscribe();

});Additional points of attention #

iOS and the subject parameter #

Even though I had everything in place now, notifications were still not working on an iOS device, while they did arrive on Firefox and Chromium. Turned out this was due to using a non-valid TLD in the subject parameter of the VAPID details.

On my local network, I’m hosting this web application on energie.villa using a static DNS entry on my router. .villa is a TLD that’s of course not known in the “outside world”. Apple doesn’t like that, so it rejected every notification I tried to send. I got an HTTP 403 along with the message BadJwtToken in the response when sending the notification to its push service. In the end, I just used my own personal domain name (sanderl.be). My backup plan was to use a mailto link instead of a URL, as those are also accepted in the subject parameter.

Using HTTPS is mandatory #

Another very important point is the mandatory use of HTTPS. Exceptions are made for localhost and 127.0.0.1 so you can test service workers while developing but once you want to go “live”, you have to come up with a proper certificate.

That’s when I learned that even though you can create a self-signed SSL certificate, it’s not enough for service workers to do their thing. They need a secure context, which can be checked in the DevTools by running window.isSecureContext. It should return true.

Local CA #

The solution was to also create my own Certificate Authority (CA). Being on macOS, I issued my package manager brew to install mkcert, a tool that would aid me in accomplishing this. Without going into much detail, the following commands were necessary on my part:

# Installs the CA in the following locations:

# - system store (that is, macOS' Keychain or Linux' /etc/ssl/certs)

# - installed browsers

# - Java

# As I don't care about Java and because it was throwing an error, I skipped it:

# keytool error: java.lang.Exception: Keystore file does not exist

TRUST_STORES=system,browsers mkcert -install

# Verify whether previous command ran fine

mkcert -CAROOT

# Actually generate the certificate

TRUST_STORES=system,browsers mkcert -cert-file "energie-villa.pem" -key-file "energie-villa-key.pem" energie.villaI’m using Nginx on my home server to serve the application, so I then proceeded by making these pem files known to it in the server block of the configuration (omitting other SSL configuration):

ssl_certificate /etc/nginx/ssl/energie-villa.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/nginx/ssl/energie-villa-key.pem;After a configuration check (nginx -t) and a restart of Nginx (systemctl reload nginx), I was able to receive notifications! The service worker was finally convinced that my domain is a safe space secure context.

Still, to get this also working on iOS, I had to import the root CA on my iPhone. To do that, I needed the rootCA.pem file mkcert generated earlier. Finding its location can be done by running mkcert -CAROOT. Copying over that pem file to my phone resulted in a message asking me whether I wanted to install the “downloaded” profile. Only one thing remained: enabling full trust for this root certificate. This can be done in Settings > General > About > Certificate Trust Settings. After this, and having added/pinned the web app to my home screen, I was finally able to receive notifications on iOS.

Localisation on iOS #

Another iOS quirk I discovered was the following. Every time you receive a notification, it’s in the form of [Notification Title] from [App Name], where from is not translated at all; it’s always in English. It doesn’t matter if your phone is set up in a different language or if you specify the lang parameter in the notification object. (Safari ignores that lang parameter anyway.) As it turns out, I’m not the only one, and you can do absolutely nothing about it.