Intro #

It happened again. Like many other evenings, I was browsing YouTube in search of new things to learn or keep up to date with various topics. That’s when this thing called ECS came up. It seems particularly useful in game development.

When developing games, a lot of different world objects exist. Seen from an architectural point of view, some of them may exist on their own, while others are part of a chain of similar objects just having some slightly different properties. That’s when you could throw object-oriented programming into the mix.

It’s a somewhat contrived example, but imagine you’ve got two classes:

RangedWeapon and MeleeWeapon, both inheriting from AbstractWeapon. An

actual weapon can then extend MeleeWeapon or RangedWeapon to get

instantiated.

So far, so good. But now suppose you’ve got this Throwing Knife weapon you want to implement. You can use it to stab some enemies, making it melee, but as its name implies you can also throw it, making it a ranged one. So now what? This is known as the diamond problem. In OO programming, you generally can’t extend from multiple base classes. (Well, in some languages like C++ you can but it can get quite ugly if you’re dealing with more advanced structures.)

Can we get around this issue using a completely different approach and pick up more benefits along the way? Yes, we can! Enter ECS.

Concept of ECS #

ECS stands for Entity Component System, each term meaning the following:

Entity #

A simple game object containing just a single unique id.

An example could be an Enemy entity. This entity by itself just contains a

unique id to be able to target it later on in the code. For example, the entity

with id 39 needs to be removed as it has been slain, for example, or the entity

with id 12 also needs to be removed as it represents a potion and it has been

consumed.

Component #

These can be associated with entities. It holds the necessary data and provides some kind of characteristic to an entity.

You could, for example, add a Damage component to all Enemy entities, which

will contain the amount and type of damage this component does. It adds a

characteristic to the Enemy entity. Of course, multiple components can be

associated with an entity. To illustrate, an Enemy entity does not only have a

Damage component but also an Animation component (as we want to display a nice

animation to the player) or a Transform component to give the enemy a position

in the game world.

System #

A system acts on all entities that may have a given component.

Let’s assume we have a Combat system that gathers all entities having the

Damage component. This system will then be able to calculate the amount of

damage the player (or some another entity) would receive.

A system can also be in charge of more technical things like animations. An

Animation system would gather all entities having an Animation component and

step through all the entity’s sprites depending on the state like “moving”,

“jumping”, etc, looping to the first frame once the last one is reached. The

frame count and duration for each frame would be specified in the component

itself.

The trigger #

I opened this post by saying I came across a video on YouTube that talked about ECS. It was shared by Dave Churchill, an associate professor of computer science at the Memorial University in Newfoundland, Canada. In fact, it was a playlist of class recordings of his course named “Intro to C++ Game Programming (COMP4300)”. Having a (non-professional and distant) past with C, C++ proves to be something quite different. Dave was not allowed to share course materials with the rest of the world but in the recordings, you were able to get what you needed to follow and complete the assignments. Well, after resolving compilation and linking errors, that is.

Initially, this went just fine. It didn’t take me too much time to implement a Geometry Wars-like game using C++ and ECS.

However, after a while, it was too hard to keep up with all the missing source and header files and I also had to look for the assets myself. You see, the students of his class get a barebones project where they have to fill in the missing pieces. I had to fill in everything myself and at some point, I just couldn’t be bothered anymore to find out what I was missing.

I stopped around the time when they started to implement a 2D platformer like Super Mario, and I thought, okay, with what I’ve learned so far, I can try and implement this myself. Using TypeScript, a language I’m more than familiar with, I can really focus on the “ECS aspect” instead of dealing with missing files and C++’s shenanigans.

Recreation in TypeScript #

Heavily based on the code of the online course, I’ll only briefly touch on the most important parts of the code.

Components #

I’ve already mentioned these components quite a few times by now and as you’ll see also our Entity class references them. What do they look like? Well, take a look at the code snippet below. It’s not the full list of components I used but it gives you an idea. It adds a characteristic while at the same time holding the required data to execute its intended behaviour.

export class TransformComponent {

public prevPosition: Vec2;

constructor(public position: Vec2, public velocity: Vec2) {

this.prevPosition = new Vec2(position.x, position.y);

}

}

export class InputComponent {

public up = false;

public left = false;

public right = false;

public canJump = true;

}

export class BoundingBoxComponent {

public halfSize: Vec2;

constructor(public size: Vec2) {

this.halfSize = new Vec2(size.x / 2, size.y / 2);

}

}

Entity #

An entity is not much more than a container holding a unique id, a tag (e.g. “enemy” or “player” for easier retrieval further on) and a collection of components that may or may not be associated with it.

There’s also this active property which is used to keep track of whether the

entity is allowed to take part in systems or not after it has been “destroyed”

or when it’s no longer necessary. If you read on, you’ll see why it’s easier to

flip a boolean when an entity should no longer be active than dealing with

removal at the time it occurs.

interface Components {

transform: TransformComponent;

input: InputComponent;

boundingBox: BoundingBoxComponent;

gravity: GravityComponent;

animation: AnimationComponent;

state: StateComponent;

}

export class Entity {

private components: Partial<Components>;

private active = true;

constructor(private id = 0, private tag: string) {

this.components = {};

}

// getters and setters...

}

EntityManager #

Of course, there needs to be something that is responsible for creating entities, updating (effectively adding and removing) them, and getting entities by tag. This will be the EntityManager that will take care of such actions.

When adding or removing entities, it’s always done in batch. As systems are

looping over entities multiple times, it wouldn’t be the best idea to suddenly

add or, worse, remove entities from an array that is looped over. That’s why

additions and removals are queued and won’t get executed until it’s safe to do

so, which is exactly what the update method is responsible for.

export class EntityManager {

private numEntities = 0;

private entityMap: Map<string, Entity[]> = new Map();

private entitiesToAdd: Entity[] = [];

public update(): void {

for (const entity of this.entitiesToAdd) {

const tag = entity.getTag();

if (!this.entityMap.has(tag)) {

this.entityMap.set(tag, []);

}

this.entityMap.get(tag)!.push(entity);

}

this.entitiesToAdd = [];

this.removeDestroyedEntities();

}

public addEntity(tag: string): Entity {

const entity = new Entity(this.numEntities++, tag);

this.entitiesToAdd.push(entity);

return entity;

}

public getEntitiesByTag(tag: string): Entity[] {

return this.entityMap.get(tag) || [];

}

public getAllEntities(): Entity[] {

const entities = Array.from(this.entityMap.values());

return entities.flat();

}

public removeDestroyedEntities(): void {

for (const [tag, entities] of this.entityMap.entries()) {

const undestroyedEntities = entities.filter((e) => e.isActive());

this.entityMap.set(tag, undestroyedEntities);

}

}

}

Game #

The class that brings everything together, instantiates stuff and is responsible for the game loop.

Let’s start with the game loop. Admittedly, that one is not fully refined. I’m

completely ignoring the delta time resulting in a faster or slower gameplay

depending on the monitor you play it on. requestAnimationFrame matches the

screen’s refresh rate so if your monitor runs at 60 Hz it’ll be updated less

(and appear slower) than when playing on a 144 Hz monitor. But to be honest,

this was not the goal of what I was trying to achieve here, so that’s why it got

neglected.

The loop itself is pretty straightforward. If the game is not paused, the entity manager should add and remove entities in batch, the input should be handled (which was set using an InputComponent) and collisions should be checked for (entities having the BoundingBoxComponent). I chose to run animations regardless of whether the game is paused or not, it’s a personal choice.

public run(time = 0): void {

// TODO: Handle different monitor refresh rates by taking `time` into account

if (!this.paused) {

this.entityManager.update();

this.handleMovement();

this.checkCollision();

}

this.handleAnimations();

this.render();

requestAnimationFrame(this.run);

}

If we take a closer look at a system, we see all the pieces of the puzzle come together. This snippet is part of the handleMovement method, taking care of gravity:

for (const entity of this.entityManager.getAllEntities()) {

const gravityComp = entity.getComponent('gravity');

const transformComp = entity.getComponent('transform');

if (transformComp) {

const prevPos = transformComp?.position;

if (gravityComp) {

transformComp.velocity.y += gravityComp.g;

transformComp.velocity.y = Math.min(transformComp.velocity.y, config.player.maxFallSpeed);

}

transformComp.position = transformComp.position.add(transformComp.velocity);

transformComp.prevPosition = prevPos;

}

}

As you can see, all entities are retrieved and then checked to see if they have a gravity component (meaning they’re subject to it, otherwise they just “float” in the air), along with the transform component. That component holds position and velocity data. If they do have these components, update the velocity and position and be done.

The same idea is applied to other systems. You get all entities, or a subset of them using tags, you check for the presence of one or more components, do some calculations based on it, update the data, and you’re done.

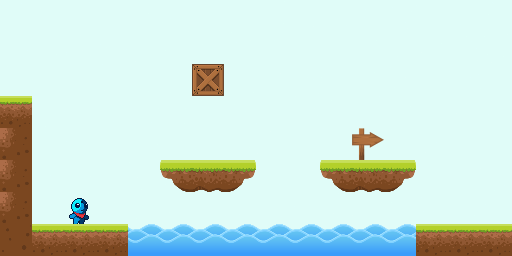

I really like the way systems interact with entities and their components. Each system has its own responsibility and kind of stands on its own, both in the code and functionally. By that, I mean that you can easily toggle certain systems on or off. The image just above illustrates that. Note that the box gets destroyed by jumping against it and will get removed from the list of entities and that the arrow sign doesn’t have a bounding box. This is why the player can walk “through” it.

Demo and other resources #

You can find a demo and the code on my GitHub repo, here.

Credits to the original artists of various assets I used and tools I used to

chop up sprite sheets can be found in the README.md of said repo.

The online shared course called “Intro to C++ Game Programming (COMP4300)” is made available through a playlist on YouTube by associate professor of computer science Dave Churchill.